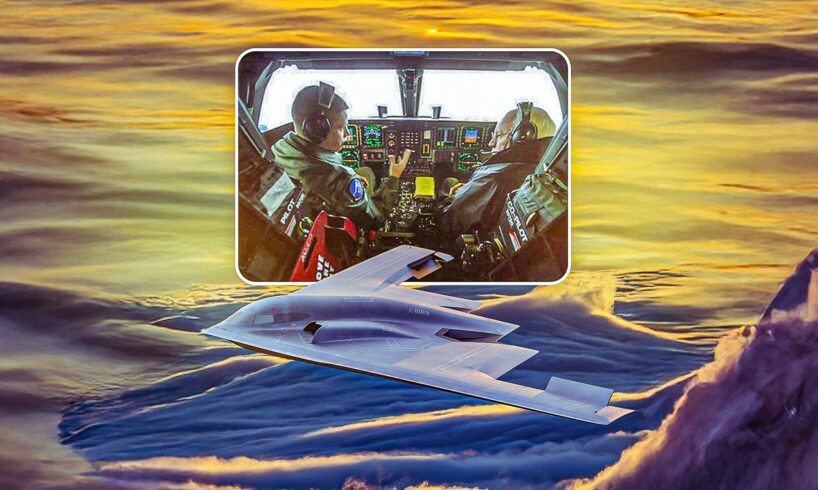

The US Air Force B-2 Spirit requires just two pilots to operate, compared with the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress and Rockwell B-1 Lancer that require a crew of four or five. The incredible computing power contained inside Northrop Grumman’s flying wing is to think for the small crew. The flight deck is also relatively simple as a result, featuring standard display screens and simple control interfaces, as the computers do most of the work while the pilots are free to focus on their mission.

Another perk of the advanced flight control systems (FCS) is that one crew member can sleep on the “camp bed” while the other flies transit legs between crucial flight phases and strike runs. The B-2 is equipped with a tiny chemical toilet, a shoebox-sized microwave, and a fold-down cot. Without the essentials of life, the Spirit’s 40-hour flights from Missouri to Libya and back, as well as its 6,000 NM unrefueled range, would be pointless.

A Flying Supercomputer

As the B-2 was made in a distinct flying wing design, which had never successfully taken flight before, its avionics system is equally sophisticated to match. The stealth-optimized bomber depends on advanced automation to allow its tiny crew to not only complete extended missions but simply to fly at all. The 172-foot wingspan bomber remains one of the most exotic aircraft ever made to date and cannot be flown without computer assistance.

Pilots are seated in the aircraft, side by side, facing a minimalistic panel in front of them. Display screens take the place of hundreds of buttons as on older planes like the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress. The most crucial one is the Vertical Situation Display (VSD), which provides the pilot with fundamental flying data, including altitude, speed, direction, and attitude. Second is the Horizontal Situation Display (HSD), which provides mission data, nearby aircraft positions, and flight path data.

The Active Electronically Scanned Array (AESA), data networks, communication systems, and fly-by-wire avionics within the B-2 are as important to success as the radar absorbent paint outside. The aircraft is updated iteratively by the “Spirit Realm” software factory that is operated by the Weapons Systems Support Center of the Air Force Life Cycle Management Center. Regular software upgrades keep the Spirit at the bleeding edge of technology while keeping pilot workload low.

The Backbone Of The Bomber Fleet

Photo: US Air Force

The US Air Force and its allies heavily rely on the B-2 to execute missions that no other platform can. A good example is in NATO’s Operation Allied Force, where Spirit crews destroyed 33% of all targets in the first eight weeks of the Kosovo Air Campaign. The B-2s of the 509th Bomb Wing at Whiteman AFB, flew less than 1% of the total sorties flown by NATO aircraft in the conflict, but accounted for 11% of the bomb load dropped. The planes dropped more than 650 Joint Direct Attack Munitions and put 90% of their bombs well within the prescribed 40 feet of their targets.

The B-2 is heavily automated and optimized for simple flying for several reasons. The first is that the flying wing can only work with computer aid; the second is that the USAF can’t afford to lose any. But a significant reason is that the B-2 crews are pushed to the limit. If you have aircrews onboard for more than 24 hours, rest becomes a necessity and not a luxury.

Lying on a canvas bunk just an arm’s length from the stick, the pilots of the B-2 Spirit do their best to sleep in the confines of their billion-dollar bomber’s bunk. The two elite pilots have to share just one camp-style cot and take turns sleeping, known as “hot racking.” Fortunately, they also have a mini-fridge and microwave to stay fed on multi-day missions. Captain Chris “Thunder” Beck, a former B-52 and B-2 pilot, told Defense News:

“After you do a few long-duration flights, anything under twenty hours doesn’t seem like a big deal.”

The mighty B-2 flying wing is currently the smallest bomber force of the US Air Force’s Global Strike Command, but conducts some of the highest profile and most prolonged mission sorties. First deployed in 1997, the 21 B-2A Spirits that were made cost more than $2 billion each. The US Air Force lost one in a crash in 2008, while another was severely damaged in 2022, leaving just 19 in the fleet today. No variants other than the first model, the B-2A, were ever made later on. As some of the most precious aircraft and military assets in existence, every effort is made to avoid damage or mistakes from human error.

Related

How Many B-2 Spirit Bombers Are Left?

The US’ B-2 stealth bomber is an awesome warplane, but how many are there?

Just Another Day Of Circling The Globe

Photo: US Air Force

The Spirit is well-known for having the longest mission duration of any platform in the US inventory. Because it can refuel while in flight, the aircraft’s range is practically limitless. The only true restriction is the endurance of the human aircrew operating the controls. The B-2 Spirit has an unrefueled range of around 6,000 NM (9,600 km), which Northrop Grumman claims is increased to 10,000 NM (18,520 km) with a single aerial refueling rendezvous.

The B-2 has very few airfields where it can land, which is not surprising given that it is one of America’s most heavily guarded military aircraft. Only in the US commonwealth of Guam, which is home to Andersen AFB, and the isolated island of Diego Garcia, a commonwealth of the United Kingdom, is it ever seen outside of the mainland US.

In response to the 9/11 attacks, the Spirit of America launched a 44-hour mission as the first volley of Operation Enduring Freedom in 2001. This sortie would go down in the history books as the longest recorded continuous flight of a military aircraft. Two B-2s simultaneously conducted identical operations, departing from Whiteman Air Force Base (AFB) in Missouri and landing on the small Indian Ocean island of Diego Garcia.

more like this

The Unique Jet Engines Powering The USAF B-2 Spirit

Much of the B-2 program is on a classified level, what we do know about the aircraft and the power plant driving this aircraft is truly remarkable.

The Limit Of Human Endurance

Former B-2 pilot, Mel Deaile’s mission after the event of September 11, 2001 (as he recounted to the USO) began with a four-hour flight from Whiteman AFB to the California coast for air refueling in the “Spirit of America.” The bomber tanked at least three times en route, including over Guam, through the Straits of Malacca, and in the Indian Ocean near Diego Garcia.

The pilots take turns sleeping in the modified “cot” beneath the two ejector seats in between refuelings. They traveled for more than twenty-four hours during the day before arriving at the Pakistani shore. By the time they reached, 70% of their objectives had been altered due to the mission’s lengthy flight profile, which involved bombing runs on several locations across Afghanistan.

The striking window was barely two hours over enemy territory after a journey of almost twenty-five hours. With four smart bombs remaining on board, the bomber left the nation and made its way to the tanker. When they were contacted and offered a new target, they were waiting for a ship in the Arabian Sea since their gas supply was running low. They left Afghanistan a second time after another ninety minutes of strike runs, this time to find a tanker ready to take them to their final destination, Diego Garcia.

The squad arrived at the small, isolated island four hours later, prepared to set foot on the ground for the first time in forty-four hours. We had to “go around,” giving the crew a 15-minute aerial tour of the island, since the B-52 that landed right before us experienced an issue. Within 45 minutes of landing, a new crew of two B-2 pilots boarded the stealth bomber, and it began its 30-hour flight back to Missouri.

The Spirit of America and five other B-2s flew continuously for about 70 hours during the American counterattacks on terrorists. Throughout the first three days, no aircraft experienced any problems or engine difficulty, which is a testament to the aircraft’s amazing engineering and design. Mel Deaile retired as a colonel, and his copilot eventually became a reserve F-22 Raptor pilot.

Related

How The US Air Force’s B-52 Fleet Maintains Global Strategic Presence

After six decades of vigilance, the US’s mighty fleet of B-52 Stratofortress’ endure to provide deterrence and ensure global security.

Stealth With Multi-Mission Flexibility

Photo: US Air Force

In the battlefield, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) is a critical role of all airborne platforms. On the battlefield, stealth aircraft have the rare capacity to go where no other aircraft can and return critical information that might mean the difference between life and death. Every operation has the potential to yield intelligence because of the capacity to monitor other troops while staying hidden.

The Northrop Grumman B-21 Raider is set to take that multi-mission, flexible configuration to an even greater extent as it is anticipated to be an optionally manned aircraft. The possibility of losing aircrews in battle is a significant risk planning consideration for Air Force operations, in addition to the danger of losing valuable aircraft and defense equipment. More mission flexibility than ever before is made possible by the B-21’s ability to enter disputed airspace without endangering human life.

To support boots on the ground, the B-2 will loiter over the conflict zone until the order for ordnance is given, which is one of the reasons it flies such lengthy missions. In addition to executing kinetic strikes, the Spirit also collects intelligence for other units during its time in active combat zones. The stealth bomber’s sensors relay vital information while the aircraft and its crew are orbiting overhead. The data gathered by the B-2 is extremely valuable to combat commanders.